New drugs less effective than old ones? Not so fast...

Want to get smarter about biotech clinical trials, R&D strategy, and financial modeling? Join the thousands of biopharma execs and professionals who subscribe to our free email newsletter. Read a sample issue, and then sign up here.

Thanks to the wonders of Twitter, David Shaywitz made me aware of a recent Reuters article by Sharon Begley with the headline, "New drugs trail many old ones in effectiveness against disease". Begley was reporting on a recent article in Health Affairs that purported to show that the relative efficacy of agents tested against placebo decreased dramatically from 1996 to 2010. From there, it was a short hop to concluding that Evil Pharma is profiting from selling glorified sugar pills:

Research published on Monday showed that the effectiveness of new drugs, as measured by comparing the response of patients on those treatments to those taking a placebo, has plummeted since the 1970s.

While that is already unwelcome news to drug and biotech companies, the consequences for the pharmaceutical industry could get worse under President Barack Obama's healthcare law.

...

In the early years, drugs easily beat the placebo: They were, on average, 4.5 times as effective, where effectiveness means how well they lowered blood pressure, vanquished tumors, lifted depression or did whatever else they were intended to.

But the trend line was inexorably downhill, found Dr Mark Olfson of Columbia University and statistician Steven Marcus of the University of Pennsylvania. By the 1980s drugs were less than four times better; by the 1990s, twice as good, and by the 2000s just 36 percent better than a placebo. Since older drugs were much superior to placebo and newer ones only slightly so, that means older drugs were generally more effective than newer ones.

"Their results are pretty compelling," said Dr Aaron Kesselheim of Harvard Medical School, who helped conduct the survey of physicians on "transformative" drugs but was not involved in this study. "It does appear that things are headed in the same direction, with newer drugs having relatively less efficacy."

...

While experts agree that tougher trials and similar factors explain some of the decline in drugs' reported effectiveness, "something real is going on here," said Olfson. "Physicians keep saying that many of the new things just aren't working as well," and therefore prescribe antidepressant drugs called tricyclics (developed in the 1950s) instead of SSRIs (from the 1980s), or diuretics (invented in the 1920s) for high blood pressure instead of newer anti-hypertensives.

Whatever the reason for many new drugs packing less punch than old ones, that will not keep them from reaching patients.

"The way the drug regulatory system is set up, even if you have just a small advance, if you market it right it can be very profitable," said [Aaron] Kesselheim [of Harvard Medical School].

Having just come from the annual ASCO cancer meeting, I'll be the first to admit that there are plenty of trial flame-outs in the modern era. But still, it seems that there are plenty of reasons why it might be hard to compare trials from the '60s and '70s to those run in this millennium. So, I figured I'd take a closer look by reproducing the authors' methodology and spot-checking the first 25 hits in 1971 and 2005. [In order not to disturb the flow of this post, I'll put my methods at the end, so those of you who want to play along at home can do what I did and hopefully add to the discussion.]

From a quick glance, there's an obvious difference between the two lists. In 1971, many of the trials appear to have been of agents that had been around for a while and used extensively in clinical practice (clofibrate, lithium, tetracycline, beta-blockers, corticosteroids, etc.); I'd guess many of them were intended to confirm and quantify effects that were seen (or at least suspected) in clinical practice. In contrast, many (most?) of the trials in 2005 were of new (unapproved or relatively recently approved) agents for which there was scant experience at the time of the trial and lot certainty of success due to new mechanisms, targets, etc. Therefore, notwithstanding the authors' efforts to demonstrate the equivalency of the trials across the decades (in terms of study design, disease severity, therapeutic area, etc.), the earlier trials appear to have had a lower technical risk.

Another interesting factor that could confound the results is the relatively high number of contemporaneous publications seeking to answer the same question. In the 1971 list above, for example, there are "duplicate" studies of azathioprine in Crohn's and lithium in affective disorders. Any amount of "double-counting" could exacerbate the differences due to technical risk I mentioned above - one success in 1971 becomes two, and one failure in 2005 becomes two as well.

I have two objections to how this played out in the Health Affairs paper and Begley's media coverage. First, I find Olfson's and Marcus's accounting of the limitations of their study somewhat cursory. I wasn't reading medical journals in 1971, but I suspect that a quick poll of experienced, grey-haired docs would yield plenty of ideas about how trials and trial publications have changed in the past few decades (including the one I illustrated here) that might have merited notice.

Second, media coverage of these sorts of studies almost always sensationalizes the results and plays to overwrought stereotypes. Begley's lede could pass for something you'd see on the supermarket checkout line: "Despite the more than $50 billion that U.S. pharmaceutical companies have spent every year since the mid-2000s to discover new medications, drugmakers have barely improved on old standbys developed decades ago." I give Begley some credit for seeking out some other opinions, but I still think it's sad but true that pharma-bashing (or implied pharma-bashing) remains in vogue at most major media outlets.

-------------

A few words on methodology:

I'm writing this from a gate at O'Hare, where I don't have (a) time to take the authors up on their offer in the article to send the full article list upon request, or (b) a team of "graduate or recent graduate students in medical epidemiology" at my disposal like the authors (see their methods). So, I took a few shortcuts. Caveat emptor.

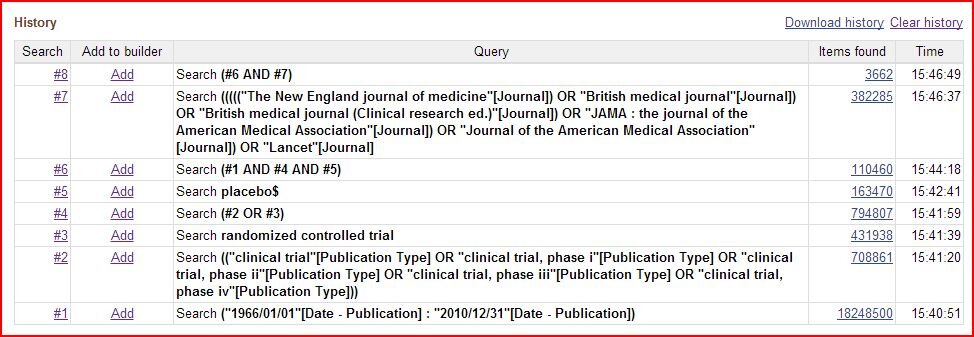

I used PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed, which I could access easity) instead of Ovid Medline (the authors' choice) - but I believe their coverage is virtually identical

I focused on two "representative" years (1971 and 2005, chosen arbitrarily), which yielded 55 and 97 articles (pre-culling), respectivey

I did a relatively cursory check of the titles to cull out reviews and obvious mis-classifications, without digging into the trial details, so it wasn't as extensive as the authors', and I'm sure there are some errors of both inclusion and exclusion

In the culled lists I decided to just look at the first 25 titles in each year to see if anything obvious jumped out

I've pasted my search results below for the entire time period below - I got 3,662 articles before further culling, compared to their 3,757 (see article appendix), which for a former consultant is essentially spot-on:

Here are my culled "first 25 articles" lists. From 1971:

Ischaemic heart disease: a secondary prevention trial using clofibrate. Report by a research committee of the Scottish Society of Physicians.

Trial of clofibrate in the treatment of ischaemic heart disease. Five-year study by a group of physicians of the Newcastle upon Tyne region.

Controlled trial of azathioprine in Crohn's disease.

Clinical evaluation of perhexiline maleate in patients with angina pectoris.

Prevention of urinary-tract infection with low-dose nitrofurantoin.

Comparative effectiveness of tetracycline and ampicillin in rosacea. A controlled trial.

Controlled trial of azathioprine in Crohn's disease.

Quinidine for prophylaxis of arrhythmias in acute myocardial infarction.

Treatment of intractable narcolepsy with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

Bronchodilator effect of oral salbutamol in asthmatics treated with corticosteroids.

Thiopropazate hydrochloride in persistent dyskinesia.

Baclofen in the treatment of spasticity.

Failure of isoprinosine in amyotropic lateral sclerosis.

Trial of maintenance therapy in schizophrenia.

Prophylactic lithium in affective disorders.

Treatment of duodenal ulcer with glycyrrhizinic-acid-reduced liquorice. A multicentre trial.

Effects of hypoglycemic agents on vascular complications in patients with adult-onset diabetes. IV. A preliminary report on phenoformin results.

Prophylactic lithium in affective disorders. Controlled trial.

Controlled comparison of the efficacy of fourteen preparations in the relief of postoperative pain.

Mebendazole in enterobiasis. Radiochemical and pilot clinical study in 1,278 subjects.

Comparison of adrenergic beta-blocking drugs in angina pectoris.

Results of double-blind, multicentre study with ritodrine in premature labour.

Therapeutic effect of 1-adamantanamine hydrochloride in naturally occurring influenza A 2 -Hong Kong infection. A controlled double-blind study.

Efficacy of lithium as acute treatment of manic-depressive illness.

Pharmacologic control of thromboembolic complications of cardiac-valve replacement.

Perhexilene maleate in treatment of angina pectoris.

Corticosteroid therapy in severe alcoholic hepatitis. A double-blind drug trial.

Effectiveness of betamethasone in management of severe infections. A double-blind study.

Study of cytotoxic chemotherapy as an adjuvant to surgery in carcinoma of the bronchus. Report by a Medical Research Council Working Party.

And from 2005:

Prophylactic Oral Amiodarone for the Prevention of Arrhythmias that Begin Early After Revascularization, Valve Replacement, or Repair: PAPABEAR: a randomized controlled trial.

Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis.

Adherence to candesartan and placebo and outcomes in chronic heart failure in the CHARM programme: double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial.

Safety and efficacy of zinc supplementation for children with HIV-1 infection in South Africa: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial.

Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis.

High-dose acetylcysteine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Sildenafil citrate therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Effects of rimonabant on metabolic risk factors in overweight patients with dyslipidemia.

Efficacy and safety of edifoligide, an E2F transcription factor decoy, for prevention of vein graft failure following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: PREVENT IV: a randomized controlled trial.

Early intravenous then oral metoprolol in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial.

Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial.

Natalizumab induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease.

Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer).

Infliximab induction and maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a phase III, multicentre, double-blind trial.

Impact of candesartan on nonfatal myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death in patients with heart failure.

Effect of BCG revaccination on incidence of tuberculosis in school-aged children in Brazil: the BCG-REVAC cluster-randomised trial.

Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial.

Drotrecogin alfa (activated) for adults with severe sepsis and a low risk of death.

Effect of weekly zinc supplements on incidence of pneumonia and diarrhoea in children younger than 2 years in an urban, low-income population in Bangladesh: randomised controlled trial.

Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition.

Comparison of a polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting stent with a bare metal stent in patients with complex coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial.

Antibacterial prophylaxis after chemotherapy for solid tumors and lymphomas.

Levofloxacin to prevent bacterial infection in patients with cancer and neutropenia.

I don't want to be accused of being (too) hypocritical, so let me get out of the way three main caveats / limitations of my "analysis". First, each item I outlined above in my methods (except the substitution of PubMed for Ovid) amounts to a sloppy methodological short-cut compared to the authors' work or any legitimate study that could get published in a peer-reviewed publication like Health Affairs. Second, because I copied the authors' underlying approach, all of the caveats of their analysis also apply to mine. Finally, and probably most importantly, I am using this "analysis" to make a rhetorical point, a fact for which I make absolutely no apologies but should be duly noted.